Argonaut Olympian Issue #6

As a club, we are honouring our past and present Olympians by documenting their achievements and establishing a permanent archive.

An Argonaut Olympian is an athlete who has been a competitive member of the club prior to competing at the Olympic Games. Until 1972, Canadian athletes represented their club as well as their country at the Olympics. By 1976, a National Team system was developed in Canada that ended club representation at the Games. Other than footnoting this difference, there is no need to further distinguish the athletes for our purposes. Under the original system, the Argonaut Rowing Club produced more Olympic crews than any other club in North America with a total of 13 crews and scullers and at least that many more gone on to Olympic glory since.

When approached to be the subject of this article, George McCauley insisted that the entire Argonaut Olympic Eight crew’s three-year career together be profiled. George is a life member of the Argonaut Club who has been involved as an athlete, manager, and archivist for 69 years.

George McCauley and the 1952 Helsinki Olympic Crew – Games of the XV Olympiad

Seventy-one years ago, George found his “sea legs” rowing inside the Toronto break wall in a Canadian Navy heavy cutter as a 14 year-old Sea Cadet. One day he witnessed an Argonaut Men’s Eight crew fly past him through the water. George thought to himself, “that’s the type of boat I should be rowing in.”

When school started at Western Tech that fall, coach Doug Wells gave an inspiring recruitment speech in the auditorium. Western Tech had produced many great Argonaut rowers in the past and most of the 90 raucous teenage boys in the audience that day signed up for a chance to row crew and compete. Wells’ speech motivated George, who had also been a champion swimmer and basketball player at Western, to try out for a crew.

In 1946, George rowed in the Western Tech Straight Four crew and won at the Canadian Schoolboy Championships. In 1947, George rowed in bow at Canadian Henley but the team was not successful. This changed in 1948, when George rowed in bow seat with another straight four to win the Canadian Schoolboy Championship once again.

In 1947, a former Argonaut champion oarsman, Harry Kaysmith, showed up at the club to assist head coach, Ken Cromwell, and immediately began to display his winning ways. In 1948, Coach Kaysmith produced a winning Junior 155 lb. Eight with George in six-seat.

At the 1949 Canadian Henley Regatta, Argonaut’s Senior 155 lb. eight, with George still in six seat, had the lead metres from the finish line when the stroke collapsed into Jack Russell’s lap causing the Argonauts to lose the race by a couple of feet. This failure to finish on stroke’s part was not acceptable to the crew and caused their immediate breakup leaving George and Jack without a crew.

Undaunted by adversity, George carried on winter training indoors on crude rowing machines with leather belts wrapped around a drum. Training paid off for George, as he was one of two Senior lightweights invited to row in the Junior Heavyweight crew in 1950. In his very first experience as stroke, George went on to win the Canadian Henley with most of his future Olympic teammates and suddenly, the dream was alive.

In 1950, it became obvious that it was Coach Kaysmith’s long-range plan to assemble a heavyweight crew to win the next Canadian Olympic trials. His disappointment, of not making the 1928 Argonaut Olympic Eight was such that he had promised himself if he couldn’t row in an Argonaut Olympic Eight, he would coach one. It was for this reason that he showed up at the Club to volunteer as a coach. Thus began Kaysmith’s long and very successful coaching career.

The 1950 Junior Heavy Eight had the necessary brawn but couldn’t seem to produce any wins and part of the reason was that the boat had five first-year men so a change was required. It was that year the CAAO changed the rules to allow two senior lightweights to row in a Junior Heavy Eight. This allowed Coach Kaysmith to invite senior lightweights George and Jack to join the Junior Eight two weeks before Canadian Henley.

This set in motion a shuffling of the crew resulting in George assuming stroke seat for the first time in his life. Coach Kaysmith then placed Jack in seven seat, a position he had for the rest of his career. This addition to the crew and a change in some other positions appeared to be the answer to the Junior Heavy Eight’s problems and this Argo crew went on to victory at the 1950 Canadian Henley Regatta.

To complete the transformation to a world-class crew, the “great” Ted Chilcott took over in bow seat. Chilcott was endorsed by the legendary John B. Kelly, who referred to him as the “best oarsman he ever knew.” Chilcott and Bo Westlake, another member of the Junior 1950 crew, had won the 1948 Olympic trials in a straight four but were not sent to the London Olympic Games. This was a sure medal win wasted.

Coach Kaysmith now had the makings of his Olympic crew that included: Ted Chilcott, Jack Taylor, Bo Westlake, Frank Young, John Sharpe, Mervin Kaye, Jack Russell, George McCauley and Norm Rowe as Cox. The crew quickly became the pride of the Argonaut Rowing Club, especially with the anticipation of the upcoming Olympics. Comparisons were even being made to the members of the bronze medal winning, 1928 Olympic Crew who were still around the club. The 1928 Olympics was also a great success for Argos Joe Wright Junior and Jack Guest, considered to be the world’s two best scullers, who combined to win silver in the double sculls.

The next two seasons included intense competition with the crew travelling to the U.S. East Coast to take on the “titans of rowing” at the New York Athletic Club, Vespers and Penn Athletic Club. In order to do this, Kelowna based boat builder, Gordon Jennins, built a shell in three pieces to be re-assembled on site wherever a race was taking place. Travelling to weekend events meant leaving on Friday night and breaking the crew into three carloads to transport the athletes, the coach and one-third of the boat strapped snugly on top of each car. They would race on Saturday and return on Sunday. This was an exhausting but exhilarating time that brought the crew together as a team. They raced hard, they jelled, and they learned to win.

1952 Olympic Trials

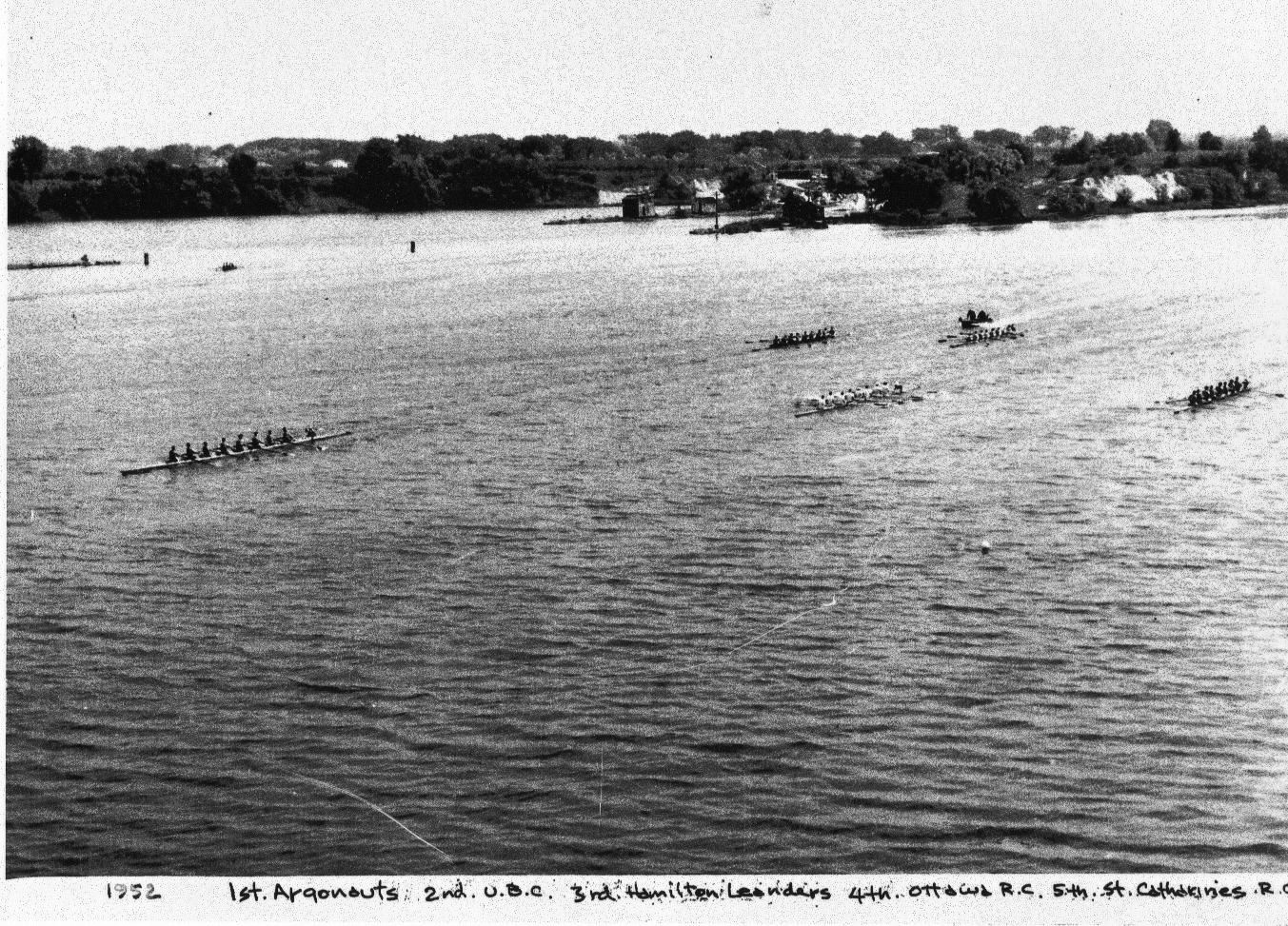

Argo heavy eight shown with a lead of almost two boats of open water over favourite U.B.C. heading towards the finish at the 1952 Olympic trials in St. Catharines, ON.

Argo heavy eight shown with a lead of almost two boats of open water over favourite U.B.C. heading towards the finish at the 1952 Olympic trials in St. Catharines, ON.

The crew descended, full of swagger, into St. Catharines for the 1952 Olympic trials. The main competition was the U.B.C. crew who didn’t know what hit them when the Argo crew engaged their trademark three and ten stroke start giving them a boat-length lead after 10 seconds. The Argos went on to win by nearly two boat-lengths of open water and won the honour of representing Canada at the Helsinki Olympics with a qualifying time faster than that of the U.S. Navy crew who went on to win the gold medal at the Games.

It was a well-kept secret that the Thursday evening before the Olympic trial race, George came down with a serious stomach flu that lasted until Saturday morning- race day. Not having a spare rower, Coach Kaysmith decided to keep George’s health condition a secret and hoped for the best. George recalls, “I hadn’t been in a boat for two days while I was sick. Coach carried the boat, the President of the club carried my socks and I was able to walk out on my own. I just kept wondering, how far could I go before I collapsed. I believe that the crew rowed the best race of their lives in part because they feared the feeble condition of their Stroke.”

After the Olympic trials, the Canadian boats, including the Argo eight, a four and a double were shipped out of Montreal in the storage hold of a freighter along with automobiles. The freighter ran into a hurricane in the North Sea that broke the cars loose from their hold and crushed all three boats into matchwood.

Hopes on hold in Helsinki

Upon their arrival in Finland, the Argo crew received the devastating news that their boat had been smashed beyond repair during the voyage across the Atlantic. Surprisingly, the news did not come from a Canadian official but rather from an Irish oarsman. The crew had to be satisfied with practice-track workouts for three days while arrangements to borrow equipment were being made with the University of Helsinki. Finnish boats were stroked from the opposite side and that had a major impact on the next days of training. The crew seating changed so that the seven seat became the stroke and the stroke moved back to seven seat and so on down the boat.

The crew had been in Finland for 13 days operating under challenging conditions and had to keep their focus on the upcoming battle with the world’s finest crews. For days, the crew ran around a practice track, and then for the next 10 days, they borrowed the University of Helsinki’s port-stroked eight with seven man, Jack Russell becoming stroke. At the same time, Coach Kaysmith was scouring Europe looking for boats with simple criteria - that they be seaworthy and with owners who would allow major alterations in order to convert from port-stroke to starboard-stroked boats. In other words, “boats that had been written off by their own clubs.”

Coach Kaysmith found a rowing club in Stockholm that had a derelict old tub of a port-stroked eight. The Canadian team accepted it and was determined to do whatever would be required to convert to starboard stroke. After almost two weeks in Helsinki, they finally got back to their regular seat positions in the wreck of the converted Swedish eight.

George McCauley decked in formal Canadian Olympian attire as he sets foot on dry land in Helsinki.

George McCauley decked in formal Canadian Olympian attire as he sets foot on dry land in Helsinki.

When he heard about the Argo situation, boat-builder Gordon Jennins paid his own way over to Helsinki to help. He agreed to carry out the necessary work to convert the Swedish boat. He worked virtually nonstop for 48 hours to complete the task. He wasn’t able to make a “silk purse out of a sows ear,” but made it possible for the crew to get back to their accustomed seats. Without the help from Gordon Jennins, the Canadian crew wouldn’t have even participated in the Games.

During these trying days, Tom Allison and Bill Ross from the Argonaut Club were trying to arrange for transport of a brand new JenCraft eight that was sitting in the Argonaut boathouse in Toronto. Club members were busy building a wooden packing crate to ship the boat to Helsinki. The crew’s spirits were lifted.

State of Euphoria Crushed

The crew’s state of euphoria was soon crushed when the plan to ship the boat was considered to be too expensive for the club. The crew was told they would have to compete in the borrowed equipment. This decision caused much debate for years with many believing that a price tag couldn’t be put an Olympic medal, especially for this promising crew.

On the Friday night, the Argonauts were finally able to take the Swedish boat for a trial row complete with six Canadian, one Swedish and one German oar. They had two practices on Saturday and their first heat against Yugoslavia, Australia, Romania and Finland took place on Sunday. George recalls the events of that day, “As the stroke of a crew renowned for their incredibly fast start out of the blocks, I am hard pressed to describe the sinking feeling when all four of our opponents in the first strokes from the starter’s flag leaped ahead of us by one full length or 62 feet. This had never happened to us before. We knew immediately that the heavy old Swedish tub had no natural run in her and that we were going to have to ‘pole her along each stroke’ playing catch up for slightly over a mile to the finish line. It took all of our strength to keep going but we did with a vengeance. I am proud to say that we passed the Finnish eight and came in fourth in the fastest heat of the day timed at 6:09:9.”

In the repechage (second chance heat) the next day, the Argonaut crew met Sweden in what turned out to be a precedent-setting Olympic rowing event. Encouraged by their performance the day before, the Canadians set out to beat the Swedish crew for a chance to advance to the semi-finals. The start was a replay of their first race and the Argonaut crew again found themselves one length down off the start but knew if they pulled together, they could finish ahead.

The First Ever “Photo-Finish”

Canadians race to the first ever photographed dead heat in the repechage against Sweden. Both teams advanced to the semi-finals of the 1952 Olympic rowing regatta in Helsinki, Finland.

Canadians race to the first ever photographed dead heat in the repechage against Sweden. Both teams advanced to the semi-finals of the 1952 Olympic rowing regatta in Helsinki, Finland.

After trailing the entire distance, the Canadian Eight gradually wore the Swedes down. They took the rate up to 40 strokes per minute in the last moments of the race and tied the Swedes on the last stroke. This was the first time that photo-finish equipment was used in Olympic rowing. The judges immediately called for a photo and after lengthy debate, a winner couldn’t be determined and the heat was declared a “tie.” Both the Canadian and Swedish teams advanced to the semi-finals.

In the semi-finals, all winners would advance to the finals and others eliminated. The Argonauts were drawn against a fine German crew. Like the other races, the Argos were left at the start and after a grueling struggle, they finished one open length behind the Germans who turned in a time of 6:19:3. Thus ended a gallant attempt by the Argonauts of Canada, against all odds, to win an Olympic medal. The determination and teamwork displayed by the Argonaut eight in the face of overwhelming adversity was much admired by the entire rowing fraternity at Helsinki. To have performed as well as the Argonauts did without any chance to win a medal drew praise from competitors, regatta officials and spectators alike. This Argonaut crew, like other Argonaut Olympic crews before them, did the Club and Canada proud.

In the history of our club, the 1952 Crew marked the end of an era as they represented the last Argonaut big-boat club entry into the Olympics as the composite and then National Team system starting replacing club-only entries.

Looking back, George says, “there was something magical about our crew. We rowed as one unit and were incredibly fast. In fact, we didn’t know how good we really were. To be the fastest starters, a crew must be totally and completely together. Our racing start was the best in the world.” Sixty-three years later, George still considers the surviving members of his crew including: Mervin Kaye, Jack Taylor, Bo Westlake, Frank Young, Jack Russell, and Normie Rowe, as his closest friends.

At the 2008 ARC boat-naming ceremony surviving members of the heavy eight are shown from back row left: Jack Taylor, Bo Westlake, Frank Young, Mervin Kaye, Jack Russell, George McCauley and Norm Rowe (coxwain).

At the 2008 ARC boat-naming ceremony surviving members of the heavy eight are shown from back row left: Jack Taylor, Bo Westlake, Frank Young, Mervin Kaye, Jack Russell, George McCauley and Norm Rowe (coxwain).

Bonded by adversity, this crew (seven of nine surviving) kept in touch and met annually throughout the decades following their adventure. At the ARC 140th birthday party in 2012, an emotional tribute was paid to, and among, the crew and there was nary a dry eye in the house.

The Rowing After-life

Still a young man post-Olympics, George became a firefighter in 1955 and remained active for 35 years. While not winning Olympic gold, George did just that in his professional career winning the honour of Canadian Firefighter of the Year in 1985. As Captain of his detachment, his truck was the first responder at a High Park apartment blaze that year. Of the two of his crew assigned to accompany him, one refused to enter the building and the other abandoned him on the way to the scene. Alone and without a mask, George grabbed the fire hose from the hallway standpipe, crawled towards the inferno and over the body of an unconscious man. George then dragged him out of the unit and to safety where he was revived and George went back to search for more victims.

George and his wife Mary (deceased), have two daughters – Nancy and Catherine and four grandchildren. He has been active at the Argonaut Club ever since his Olympic adventure; first as club Secretary for many years, then General Manager, and later in life tending to our archives and enabling us to access our rich history of competition dating to 1872. Our large, back-bar picture features this very crew rowing to a dead heat in Helsinki.

George McCauley - Rowing Biography, Notable Achievements

BIO & Selected Notable Achievements

- 1929 - Born in Toronto, ON

- 1945 - Attended Western Technical and Commercial School

- 1946 - Joined high school rowing squad

- 1946 - GOLD Canadian Schoolboy Jr. Men's 4-

- 1948 - GOLD Canadian Schoolboy Sr. Men's 4-

- 1948 - GOLD - Canadian Henley in Jr. Ltwt Eight

- 1950 - GOLD - Canadian Henley in Jr. Men’s Eight

- 1951 - GOLD in U.S. Middlestates Regatta in Sr. Men’s Eight

- 1952 - GOLD – Canadian Olympic Trials

- 1952 – eliminated in semi-finals – Helsinki Olympic Games

Grant Sommers